Brief to House of Commons Standing Committee on Health – Parliament of Canada

From Registration to Retention: Supporting Internationally Educated Nurses Through Quality Bridging Education and Integration Support

A Note on Terminology

This briefing note refers to the nursing professions in Canada, which include licensed practical nurses (LPNs), registered psychiatric nurses (RPNs), registered nurses (RNs), and nurse practitioners (NPs).

In Ontario, the designation for diploma-prepared nurses is registered practical nurse. In this note, we use LPNs when referring to practical nurses across Canada.

Background

Concerns surrounding the domestic production of nurses are not new. In 2018, forecasting models predicted that Canada would face a shortage of 117,600 nurses by 2030 (Scheffler & Arnold, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic introduced conditions that accelerated retirements and other attrition from the nursing workforce.

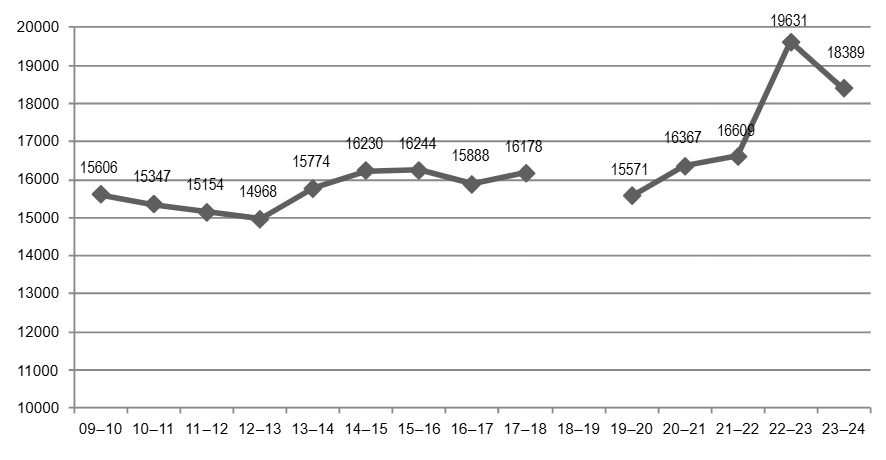

Nursing programs have increased seats in response to the rising demand for LPNs, RNs, and NPs. For example, from 2009–2020, program seats in entry-to-practice programs for RNs remained stable, admitting an average of 15,696 students annually (Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing [CASN], in press). A notable 12% increase occurred between 2021 and 2024, with programs admitting 18,389 students (see Figure 1). During this period, seats in NP programs increased by 41%. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) reported growth in the supply of both LPNs and RPNs in 2023 and 2024 (CIHI, 2025a, 2025b).

Recent projections of health workforce supply to 2034 identified a persistent gap, with the largest shortage expected among RNs (Health Canada, 2025). Although expanding the domestic production of nurses is a sustainable and ethical strategy, it must be considered alongside the broader potential workforce, including IENs.

Figure 1

Admissions to Entry-to-Practice RN Programs, 2009–2010 to 2023–2024

Source: CASN (in press).

Since well before the pandemic, Canada has been a destination for IENs. While the immigration system has made it easier for this highly skilled workforce to enter the country, fewer resources have been dedicated to ensuring they are able to transition into employment that matches their education (Covell et al., 2017; OECD, 2019). Over half of recently immigrated IENs work as orderlies, nurse’s aides or LPNs, despite holding a bachelor’s degree or higher. (Bernard & Seddiki, 2025). This underutilization of IENs represents “brain drain,” the loss of nurses from a country’s health system due to migration, and “brain waste,” the underuse of nursing skills after migration. is misaligned with international guidance for ethical immigration of health professionals (Walton-Roberts et al., 2014).

To practise nursing in Canada, IENs must obtain licensure from a provincial or territorial regulatory body for nursing. Historically, the pathway from application to registration and licensure was challenging costly, leading to attrition of IENs from the process (Blythe & Baumann, 2009; Lee & Wojtiuk, 2021).

When the nursing shortage rapidly escalated during the COVID-19 pandemic, the nursing regulatory bodies streamlined the processes surrounding the application and registration of IENs (Chui et al., 2025). These reforms have led to growth in IEN registrations across jurisdictions and in all categories of nursing. The proportion of IENs in Canada grew from 8% of the nursing workforce in 2017 to 12% in 2022 (CIHI, 2024).

An increase in IEN applicants and faster application processing has increased demand for bridging education. Research supports bridging education that is flexible and accounts for the IEN learners’ needs and their previous nursing experience, with an emphasis on clinical practice opportunities (Neiterman et al., 2018; Sanders et al., 2025). Provincial governments, regulatory colleges, and post-secondary institutions have responded to the increased demand and challenges associated with the rigidity of existing bridging education by developing targeted, expedited bridging education (e.g., accelerated pathways for IENs at Saskatchewan Polytechnic; the Ontario Colleges IEN Upgrade Courses).Changes to bridging education have varied across the country and reflect the availability of resources provincially.

Attrition of the nursing workforce remains a reality that must be considered alongside IEN integration and retention. 4 in 10 nurses intend to leave the profession within the next year (Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, 2024) and 40% of nurses are leaving the profession before the age of 35 (Faubert, 2025). In Ontario, IENs were less likely to renew their registration and be employed in nursing compared to graduates educated in Ontario (CNO, 2024). Reasons for this higher rate of attrition are not well understood.

Considerations for the Committee

Recent streamlining of the IEN application and registration reflects the implementation of long-overdue reforms (Crea-Arsenio et al., 2023). Research is needed to understand the impacts of reforms to identify best practices in IEN application and registration. Further harmonization across provinces in these processes could also reduce confusion and create a more equitable process for all IENs seeking nursing registration in Canada (Chiu et al., 2025).

IEN bridging education is beneficial for preparing IENs for nursing practice in Canada and supports their long-term retention (Covell et al., 2018). Evaluating the outcomes of reformed targeted bridging education of IENs is necessary to understand best practices and future directions. These best practices should be integrated into standards for program approval and accreditation processes to ensure quality and lessen variable outcomes.

Health care institutions require access to reliable and accessible transition support programming, particularly for IENs who transition directly from another country into nursing practice in Canada. Common learning needs include communication barriers, unfamiliarity with the Canadian health care culture and the autonomous yet interprofessional nature of Canadian nursing practice (McGillis Hall et al., 2015; Ramji & Etowa, 2018). IENs encounter interpersonal and systemic racism that affects their transition and work experience. Nurses that are made aware of these experiences and are trained in culturally safe mentorship contribute to inclusive workplaces (Cruz et al., 2025). Given that there is a lower rate of registration renewal amongst IENs, it is important to ensure investments in improving registration processes and bridging education pathways are not wasted.

Recommendations

CASN respectfully requests that the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health consider the following actions:

- Create a national joint commission on IENs to further optimize registration, bridging, and transition supports for IENs.

That a joint commission be established between provincial and territorial nursing regulatory bodies, CASN, the Canadian Nurses Association, Chief Nurses Officers/Executives, and Canada’s Chief Nursing Officer to work in a coordinated, pan-Canadian effort to strength IEN registration, bridging education, and integration.

This joint commission could work to:

-

- coordinate actions between systems that support IENs from application through to employment to further streamline entry to practice;

- evaluate the outcomes of recent reforms to identify best practices and strive towards implementation across jurisdictions where feasible; and

- explore innovative solutions, such as IEN residency or accreditation of international schools.

- Support continued improvement of IEN bridging education.

That the Foreign Credential Recognition Program (FCRP) support regulatory authorities and schools of nursing in building flexible and targeted bridging education for IENs that recognizes the competencies the IENs already possess. The outcomes of these programs should be evaluated and support approval and accreditation processes of IEN bridging education.

- Support integration programming for IENs.

That the FCRP support institutions in strengthening their capacity to effectively integrate IENs through structured, accessible programs, such as CASN’s IEN Mentorship Program.

Conclusion

The World Health Organization (2025) predicts a global nursing shortage of 4.5 million nurses by 2030. Canada must implement ethical and sustainable solutions now to meet our domestic needs. The support of IEN integration should be seen as one element of a broader necessary HHR strategy for nursing that includes domestic production, providing transition supports for new graduates, cultivating healthy work environments, and enabling nurses to practise to their full scope.

About the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing

CASN is a non-profit organization that leads nursing education in the interest of healthier Canadians. CASN represents 93 member schools of nursing. CASN plays a central role in ensuring excellence and continuous quality improvement in nursing education through its voluntary national accreditation program, which includes a specialized accreditation stream for IEN bridging programs. In 2024, CASN launched the IEN Mentorship Program, designed to strengthen the successful integration of IENs into the Canadian health care system. Together, these initiatives position CASN as a national leader in best practices for IEN bridging education, transition, and integration support.

For more information:

Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing

Website: www.casn.ca

References

- Bernard, A., & Seddiki, Y. (2025, April 10). Insights on Canadian society: Workforce renewal in health occupations. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2025001/article/00006-eng.htm

- Blythe, J., & Baumann, A. (2009). Internationally educated nurses: Profiling workforce diversity. International Nursing Review, 56(2), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00699.x

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing. Registered nurses education in Canada statistics, 2023–2024 — registered nurse workforce, Canadian production: Potential new supply. https://www.casn.ca/2025/12/registered-nurses-education-in-canada-statistics-2023-2024/

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. (2024). CFNU member survey report. https://nursesunions.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024-CFNU-Members-Survey-Web-1.pdf

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2024, February 29). Internationally educated health professionals. https://www.cihi.ca/en/the-state-of-the-health-workforce-in-canada-2022/internationally-educated-health-professionals

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025a, July 24). Licensed practical nurses. https://www.cihi.ca/en/licensed-practical-nurses

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2025b, July 24). Registered psychiatric nurses. https://www.cihi.ca/en/registered-psychiatric-nurses

- Chiu, P., Alostaz, N., Hermosisima, A., Li, R., Ben-Ahmed, H. E., Atanackovic, J., Iduye, D., Thiessen, N., Salami, B., & Leslie, K. (2025). Licensure pathways for internationally educated nurses: An environmental scan of Canadian nursing regulatory bodies. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 16(2), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnr.2025.06.004

- College of Nurses of Ontario. (2024). Nursing statistics report: 2024. https://www.cno.org/Assets/CNO/Documents/Statistics/latest-reports/nursing-statistics-report-2024.pdf

- Covell, C., Primeau, M.-D., Kilpatrick, K., & St-Pierre, I. (2017). Internationally educated nurses in Canada: Predictors of workforce integration. Human Resources for Health, 15, Article 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0201-8

- Covell, C., Primeau, M. D., & St-Pierre, I. (2018). Internationally educated nurses in Canada: perceived benefits of bridging programme participation. International Nursing Review, 65(3), 400–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12430

- Crea-Arsenio, M., Baumann, A., & Blythe, J. (2023). The changing profile of the internationally educated nurse workforce: Post-pandemic implications for health human resource planning. Healthcare Management Forum, 36(6), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/08404704231198026

- Cruz, E., Tay, J., Bradley, P., & Baxter, C. (2025). Supporting internationally educated nurses through effective preceptorship: A Canadian perspective. Journal of the Society of Internationally Educated Nurses, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.31542/y4tw3g36

- Faubert, E. B. (2025, October 22). The evolution of the nursing supply in Canada. Montreal Economic Institute. https://www.iedm.org/the-evolution-of-the-nursing-supply-in-canada/

- Health Canada. (2025). Caring for Canadians: Canada’s future health workforce – the Canadian health workforce education, training and distribution study; executive summary. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/health-human-resources/workforce-education-training-distribution-study.html

- Lee, R., & Wojtiuk, R. (2021). Commentary – transition of internationally educated nurses into practice: What we need to do to evolve as an inclusive profession over the next decade. Nursing Leadership, 34(4), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2021.26689

- McGillis Hall, L., Jones, C., Lalonde, M., Strudwick, G., & McDonald, B. (2015). Not very welcoming: A survey of internationally educated nurses employed in Canada. GSTF Journal of Nursing and Health Care, 2, Article 21. https://doi.org/10.7603/s40743-015-0021-7

- Neiterman, E., Bourgeault, I., Peters, J., Esses, V., Dever, E., Gropper, R., Nielsen, C., Kelland, J., & Sattler, P. (2018). Best practices in bridging education: Multiple case study evaluation of postsecondary bridging programs for internationally educated health professionals. Journal of Allied Health, 47(1), e23–e28.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Recruiting immigrant workers: Canada 2019. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/recruiting-immigrant-workers-canada-2019_4abab00d-en.html

- Ramji, Z., & Etowa, J. (2018). Workplace integration: Key considerations for internationally educated nurses and employers. Administrative Sciences, 8(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8010002

- Sanders, C., Roots, A., Hoot, T., Haggarty, D., Howell, M., Clyne, C., Vostanis, A., Agoston, I., Huynh, N., Bell, A., & Sokolowski, V. (2025). Nurse bridging education: Optimization, innovation and sustainability. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391561517_Nurse_Bridging_Education_Final_Report

- Scheffler, R. M., & Arnold, D. R. (2019). Projecting shortages and surpluses of doctors and nurses in the OECD: What looms ahead. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 14(2), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/s174413311700055x

- Walton-Roberts, M., Williams, K., Guo, J., & Hennebry, J. (2014). Backgrounder on immigration policy changes and entry to practice routes for internationally educated nurses (IENs) entering Canada. International Migration Research Centre. https://scholars.wlu.ca/imrc/10/

- World Health Organization. (2025, July 17). Nursing and midwifery. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery

Download the CASN Brief to the HOC HESA

Related Resources:

- CASN President-Elect Testifies Before House of Commons on Nursing Workforce Crisis and IEN Integration (January 2026)

- CASN ED Appears as Panel Witness for House of Commons on Reforms to the International Student Program (December 2024)

- Effects of International Student Cap on Schools of Nursing – Brief to House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (CIMM) (January 2025)